Emerging from the flood, Appalshop's WMMT reflects a dynamic Appalachia

Appalshop and its radio station help imagine possibilities and empower the next generation of Appalachians

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” Arthur C. Clarke famously wrote. But some magic is better than others. It’s not just the whiz-bang factor that makes it good.

The best magic? When technology is harnessed by people who care about each other and used to nourish relationships. The best magic is when people can be fully human in one another’s presence - enabled by tech that makes it possible across the many miles and the walls (literal and metaphorical) that divide us.

* * * * *

It’s a humid evening in Whitesburg in Letcher County, Kentucky. I’ve just had an early dinner with the staff of WMMT “Possum Radio,” the community radio station licensed to a storied nonprofit called Appalshop. WMMT’s General Manager T Wimer shows me to the Possum Den — the used RV that has served as their air studio for the last two years.

Inside the RV, I find a fully functioning radio station with two studios, rather snug as they may be. DJ Geonoah Davis is playing an all-request show — mostly rap, R&B, and rock on this evening. The requests are coming in by phone and social media, and they’re coming in from all over the country. They’re all coming from people who have loved ones in prison. Callers who want to share a favorite song with an inmate who they care about.

Looming over Whitesburg is Pine Mountain, and perched at more than 3,000 feet above sea level is WMMT’s transmitter & antenna. On the other side of the ridge, Wise County, Virginia is home to two supermax prisons. Those inmates are the intended audience for this show, “Tunes From Home.”

“Tunes From Home” and its sister program “Calls From Home” make up WMMT’s project Restorative Radio. Its genesis traces back to 1999 when WMMT hip hop DJ VIP (Virgil Prinkleton) got a call one night from a person trying to leave a shoutout for someone inside. The DJ aired that call. From there, the station made the unusual decision to serve the prisoners instead of ignore them. To treat them and their families as human beings and members of their community. Almost a quarter-century later, it’s still going. There’s a film about it.

During the two-hour music show, WMMT’s then-Programming Coordinator takes calls from families. Most are repeat callers who she’s gotten to know. She hears about a kid’s birthday party, and evidently California is still experiencing a major heat wave. She transfers the calls to an audio mixer, records phone messages from family members, and splices them together into one long file to air at 9 p.m.

Most people will never get to sit in an RV-turned-studio in rural eastern Kentucky. Most people will never get to answer the phone when people call in to send radio messages to loved ones. Most people will never get to cast those voices down the mountain, over the forests, through the air, through barbed wire fences, through concrete walls and bars, and into the ears of inmates. Voices that provide a source of human connection to people who are so starved of connection because they’re in prison and that’s what our carceral state does.

To be an observer of that… Well, it feels like some pretty great magic.

* * * * *

Like of the rest of this part of Appalachia, Letcher County’s story is tied up with the coal industry. When coal companies arrived in the early 1900s, the population swelled from 10,000 to 40,000. The incredible wealth buried in the mountains was shipped out to fuel America’s mid-century prosperity. Coal company owners profited mightily. When industry changes led to far fewer jobs, those coal companies left behind swaths of deep poverty, little infrastructure, and a mono-economy where little else could develop.

Harry Caudill was a lawyer, state legislator, and Letcher County native descended from the original white settler families. In 1963, he published “Night Comes to the Cumberlands,” a monumental history of the region and the effects of coal. The book made a big impact and shined a national spotlight on the plight of Appalachian residents. A year later, President Lyndon Johnson made Appalachia a keystone of his War on Poverty.

One program of the War on Poverty was a series of 10 Community Film Workshops. In 1969, the Appalachian Film Workshop opened in Whitesburg, training young people in filmmaking and producing films about the region. Appalshop, which incorporated as an independent non-profit in 1974, is one of only two film workshops that survived.

When people rely on outsiders to tell their stories, the outsiders often get it wrong. Or the stories don’t get told at all.

At Appalshop, people of Appalachia tell their own stories in their own voices. They share their own music and art — both lasting traditions and contemporary creativity. They work toward solving their own problems in their own ways. And they’ve been doing it for more than half a century.

What will the next half-century bring?

* * * * *

It rained hard on July 25, 2022 and the creeks filled up.

It kept raining and the creeks jumped their banks.

It kept raining and the hollers became a wall of water.

It kept raining. Cars and homes washed away.

It kept raining. People got killed.

It kept raining. Schools and businesses flooded, filled with river muck.

One of those was Appalshop. WMMT’s studio and all its gear, located on the ground floor, was submerged in chest-high water.

The two-year anniversary of the floods is just around the corner. T tells me they’re feeling skittish. They get nervous anytime it rains hard.

The building has been mostly cleared out, but you can still see the water line between “WM” and “FM.”

Things were worse still for Nik Lee. She’s one of the instructors this summer for the Appalachian Media Institute (AMI), Appalshop’s flagship film education program for young people. For her, the flood meant losing not just her workplace but also her home.

“It starting getting bad at 2 AM,” Nik says in Appalshop’s documentary All Is Not Lost. “It was raining pretty hard and my mom was like, ‘We have to leave, the water is getting in the garage.’ We decided we were going to try to go out of the holler to see how high the river was getting. We got to the end of our fence and we couldn’t get any further because the rocks and all were washed over in the road. Within probably 30 minutes, it was coming up over the bank behind the house. And then probably another 30 minutes, it was up on the porch and then in the house. It was so fast.”

In the weeks that followed, everyone who could pitched in to clear the roads. A lot of people volunteered to clear out the Appalshop archives.

“Appalshop people were very active with mutual aid groups,” says T. From distribution houses filled with emergency supplies, Appalshop employees drove stuff out to access points. “WMMT’s entire story today is predicated on the flood. It affected everybody, personally and professionally.”

(Pictured below: T (right), Nik (center), and Madison Buchanan (left), Nik’s fellow AMI instructor.)

* * * * *

It’s now two years since the flood. Things move forward.

Appalshop moved its headquarters 15 miles down the road to a former hospital building in Jenkins, KY. It’s above the floodplain.

Appalshop’s archives were also on the first floor of the old Whitesburg headquarters. Thousands of films and artifacts were damanged in the flood. Shane Terry is the Archives Operations Tech and is working with the American Archive of Public Broadcasting to digitize everything that was ever part of a broadcast. He also built out WMMT’s RV studio.

Mimi Pickering directs Appalshop’s Community Media Initiative and has been making films there for 50 years. Her catalog of film projects is tremendous - from modeling post-coal posssibilities to local agriculture to public health storytelling projects around reproductive health and diabetes prevention. And lots more besides.

“Stories from people here who sound like here have more resonance and impact,” says Mimi.

She has also hosted a string of WMMT shows over the years: Biscuits & Gravy, Biscuits & Ham, Biscuits & Pop Tart, and Biscuits. Mimi is Biscuits. The co-hosts may change, but the shows have always featured lots of women country & Americana artists.

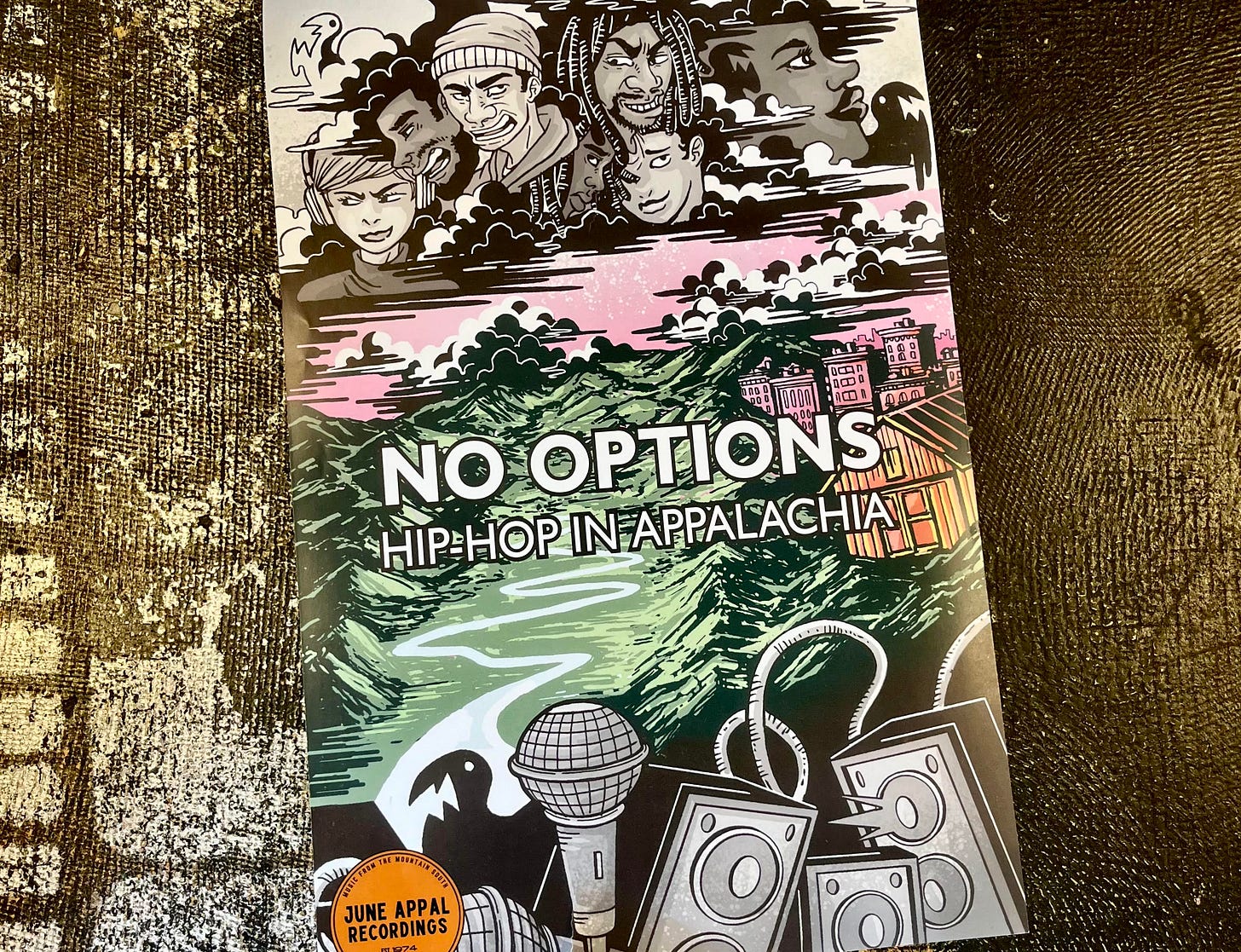

Besides managing WMMT, T’s job also includes overseeing Appalshop’s record label, June Appal. While the label has primarily released bluegrass, old time, blues, roots, and folk music over the years, they've just released a new hip hop album: “No Options: Hip Hop in Appalachia.”

In 24 tracks, No Options explores the range and diversity of hip-hop in Appalachia. Geonoah (from the “Tunes From Home” show) is one of the artists.

Nik and Madison, who were students in AMI just a few years ago, now teach the program.

“I used to see this region through a very narrow lens. This is an opportunity to stay, to do creative work and grow to love the region,” says Madison. “That’s true for kids here at AMI, too.”

“Lots of young people who want things to change and improve end up leaving, going to Lexington or other cities,” she continues. “People with good ideas don’t see a possibility to stay, put time in, and change. So we don’t have the sustained efforts at the changes we need.”

* * * * *

Tommy Anderson’s title is Administrative & Programmatic Generalist. What that means is that they sort of grew up in Appalshop, know all the personalities here, and have worked for all parts of the shop.

Tommy explains that Appalshop is really going through three overlapping transitions right now:

The physical space, obviously, since the flood.

A generational shift from its founders to younger generations

The changing tech of media and how people use it

“What do we do in an era of TikTok and whatever bigger fish will come along and eat it? Is radio a beautiful, ancient whale singing a song that will always wander the ocean lonely?”

Tommy can turn a phrase.

But the media landscape really is changing, so fast and hard that it can be difficult to pause, step back, and take stock. And the legacy of WMMT’s founding staff casts a long shadow. Tommy says that program manager Jim Webb was the “spiritual nucleus of WMMT” from its founding in 1985 until his passing in 2018. “The transition was handled mostly gracefully, but it feels like young people woke up in their parents’ or grandparents’ body.”

As a core of Appalshop’s mission, it has always taught young people media production skills and helped them imagine possibilities for staying in the region.

And unlike so many institutions, Appalshop today really is bringing younger people into leadership roles. Tommy and Shane are in their 30s. T, Nik, and Madison are in their 20s.

From what I see, it seems like a lot of the folks at Appalshop have their eye on the ball. To remain relevant, our organizations need to serve community needs and educate & empower young people. To do that, we must approach our work more as community organizers than “broadcasters” per se.

Still, tough questions keep crossing my mind.

Can a media nonprofit create enough opportunities for young people to stay?

Can it counter the tide on economic trends that are leading to depopulation of a region?

Can it be a hub that connects the many thousands of “Expat-alachians” to their home? To remain relevant to both the local communities and those communities that no longer live locally? How much and how long with those expat folks still try to stay connected?

And can it sustain itself and pay the bills for this important work?

* * * * *

During my visit, Appalshop finalized a deal for WMMT to move its studios into a rather roomy storefront in downtown Whitesburg. Certainly a lot roomier than an RV. The studio build starts soon.

It’ll be a fine place to make some magic.

What a very nice read this morning over my coffee! Thank you for your writing!

We had quite a bit of water in Staunton last night. My partner and I spent the night on flood watch in our building downtown; it was nothing like Whitesburg in 2022.

We lived in the Pennyrile region of Kentucky for many years and discovered WMMT, The Appalshop and Night Comes to the Cumberlands as part of our nearly two decades of travels in the great state of Kentucky. Your writing brought back good memories of those discoveries.

Thank you, Appal Shop, for decades of great work in the world. Love this inspiring story of resilience and powerful intention!